The Last Conductor of Kuhio Avenue: The Life of George Josserme

A Chance Encounter in Kapiolani Park

Every evening, I walk through Kapiolani Park in Honolulu. It’s a place of banyan trees, ocean breezes, and quiet reflection. During mango season, the trees around Paki House were heavy with fruit, and I often found myself lingering in the backyard, drawn by the sight of a ripe, golden mango dangling temptingly within reach.

One day, as I knelt to pick a juicy mango, an older man approached silently and handed me two perfect ones. His eyes twinkled with kindness. That was my first encounter with George Josserme.

From that moment, he became a regular part of my walks. My wife and I often talked about him—he seemed mysterious, dignified, and somehow out of place. He sat at the bus stop near the big trees, looking comfortable, not quite homeless but not fully part of the neighborhood either.

One evening, I decided to say hello. We spoke about mangoes, and I heard his accent—foreign but familiar. He told me he was born in Marseille, France, in 1947, after his parents returned following World War II. During the war, they had been active members of the French resistance. His mother, skilled in Morse code, spent long hours near the Marseille port, watching for German submarine activity and passing critical intelligence to British forces—helping them anticipate attacks on their ships near Gibraltar. Their covert efforts didn’t go unnoticed by the Nazis, who eventually sought to capture them. In gratitude for their bravery, the British offered them refuge in Britain until the war ended. While living among Allied troops and civilians, George’s parents formed a deep respect for the American and British forces, a sentiment they often expressed as he was growing up. Those stories shaped George’s early view of the world and sparked his lifelong curiosity about England and the United States.. George was born years after the war, but his parents often spoke with admiration about the kindness and courage of the Allied forces during their time in Britain. Their stories left a deep impression on him, planting the seeds of a lifelong curiosity about England and, eventually, the United States. When I asked what brought him to this beautiful island, he traced that journey back to those early tales of wartime generosity.

George later moved to Britain, married, and had two daughters. But life became difficult. After a divorce and strained relationships with his daughters, he left before they married. They don’t know he came to Hawaii.

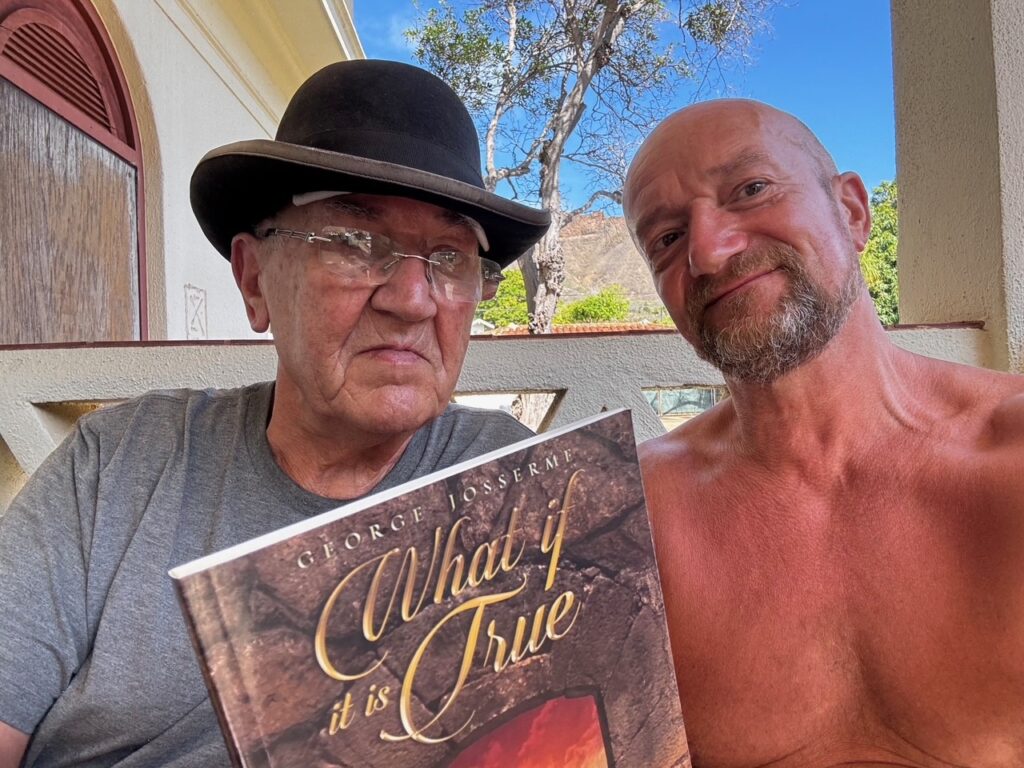

He told me he had worked as a conductor of philharmonic orchestras and began writing at the request of an editor who admired his storytelling. He didn’t plan to write many books, but the stories were too close to his heart. He kept writing—and has now published four titles: What If It Is True, Straight Up To The Stars, Stardom To Gloominess, and Oak Trees Die Standing Up.

In What If It Is True, George describes how he began his musical journey as a violinist, eventually rising to become a conductor of philharmonic orchestras. The book opens with a man deeply in love with his wife, living a life of refinement and artistic purpose. Later, when life delivers a profound emotional blow, he draws upon the analytical faculties he developed during his conducting career to process and transform that experience.

During our conversation at the bus stop, he promised to bring me a copy of his first book the next day. True to his word, he handed me What If It Is True during my afternoon workout walk in the park. We took photos together on the porch of Paki House, with Diamond Head in the background. He explained the book’s premise, and I recorded his words—linked here for those who wish to hear his voice.

The following day, I found him sitting on the lanai of the Paki House office building. The office staff let him stay there during the day, and he’s treated like a regular. As we sat on the bench talking, employees walking in and out greeted us with a nod. He spends most of his day on the porch, continuing to write new books.

But at night, George returns to the bus stop bench, where he’s slept for the past 15 years. One day, as we sat together, he pointed to the sign that read:

“No lying down in bus shelter or bus stop area.”

Then he smiled and said the police make an exception for him. A quiet nod to the Aloha spirit of the Honolulu Police Department. A patrol car with flashing lights parks nearby each night, and he told me it’s safe—no one can approach with evil intent. The officers know him. He’s not an addict or a criminal. He’s a man of standards.

That day, I asked if I should raise public awareness about his situation to help him move into an apartment. He gently declined and shared the story behind his homelessness.

The local government once provided him with a subsidized apartment for $130 a month—an amount he could easily afford. But the problem was the neighbors. When he politely asked them to turn down their music, one threatened to break his head open. Fearing for his life, George returned the key to the receptionist and walked away.

He doesn’t want bad people around him. He can’t stand confrontation. At this age, he wants peace.

Others have tried to help. One man paid $600 for his rent, but the apartment came with a roommate—a Filipino woman who stole his laptop containing all his work. George went to court but never got it back. That experience sealed his decision: he’d rather live in the park than risk losing his peace or his dignity.

He told me that sometimes people passing the bus stop bring him food from nearby restaurants. He always accepts politely—but the food ends up in the garbage. He doesn’t eat Chinese, Vietnamese, or Korean food. He appreciates only quality French cuisine. When I asked where he finds it on the island, he said, “Nowhere.” But he eats healthy—fruits, vegetables, simple and clean.

Sometimes, people approach him with a cheerful “Hi George!” but he finds them too intrusive. Without a word, he points to his mouth, mimicking a toothache to avoid conversation. I joked to myself that next time he does that, I’ll know it’s my cue to walk away. But he liked me. He told me he wants only good people around him—“people like you.” It felt good to know he had a high opinion of me.

George also mentioned that he has lots of belongings and pays $400 a month for a storage unit, which he visits daily when he needs something. That’s where he keeps his violin. He kindly offered to play it for my wife and me the next time we walk by together. It was a generous gesture, and I appreciated it deeply—both of us love classical music, especially the sound of the violin. Hearing it from someone like George, a seasoned violinist and conductor, would be a rare and beautiful experience.

After a few days, I stopped by to say hi to George. He was watering the grass behind the historic building before his usual daily shower. It’s like a ritual to him, and he always does it when I pass by at the end of the day before sunset—my favorite time for walking around Kapiolani Park.

I offered my phone number and encouraged him to contact me if he needed help or assistance. We exchanged numbers.

The next day, George texted me to ask for a small favor: would I keep a bottle of his supplements in my refrigerator? He had accidentally purchased extras and was concerned they might deteriorate. He’d even consulted the pharmacist, who advised refrigeration. Ever thoughtful, George wrote,

“Please, Stefan, do not feel obligated to accept. Maybe your wife may not like it.”

I was so happy to receive his message. It felt like more than a logistical request—it was a gesture of trust. It gave me a reason to visit him again. And honestly, I couldn’t wait. His storytelling skills are fantastic—complex, visual, filled with elegant phrasing and unexpected turns. I wanted to know everything about this great man, this philosopher of the bench.

As I agreed to help, he thanked me profusely, as always.

This chapter isn’t just about meeting a man in the park. It’s about meeting someone who refuses to be defined by circumstance. Someone who lives by his own code, even if that means sleeping on a bench and showering with a hose.

It’s about earning the trust of a man who’s built his life on solitude and principle—and finding a story that deserves to be told, chapter by chapter.

And it’s only the beginning.

I returned to Paki House in the late afternoon, my usual time for walking through Kapiolani Park. The breeze had softened, and golden light spilled across the lawn as I stepped onto the porch of the historic building. George sat there, as he often does—calm, thoughtful, and dignified.

He handed me a small bag containing the vitamin supplements I’d offered to keep in my refrigerator. It was a simple gesture, yet it marked something deeper: a growing bond built on trust and mutual respect.

When I asked how he was doing, George didn’t complain. He rarely does. Instead, he spoke with clarity and reflection about the hardships of homelessness—not as a victim, but as a man who’s made deliberate choices to preserve his peace. “I’d rather be alone than around bad people,” he said. “I value my energy.”

He then told me about a disturbing rise in attacks on homeless individuals around Waikiki Beach. The police had advised him not to sleep there anymore. “They told me the back terrace of Paki House would be safer,” he said. “There’s a patrol car parked in the courtyard most nights. No one can slip through without being seen.”

For more than a year, George followed that advice. He slept on the terrace quietly, unobtrusively, watched over by the same officers who appreciated his integrity.

But one night, everything changed.

Unaware of George’s routine and unfamiliar with his reputation, a new officer approached him aggressively in the middle of the night. Without a word, he woke George by pounding his head with closed fists. George spent the entire next day battling a splitting headache, not just from the blows, but from the humiliation of being treated like an intruder in what had become his peaceful refuge.

When the other officers found out what happened, they apologized earnestly. “There are still bad seeds in the department,” they told him. “It’s hard for the city to root them out.” They meant well, but George had made up his mind. From that night forward, he stopped sleeping on the back terrace.

Instead, he returned to the bench at the bus stop just outside the courtyard—his new nighttime refuge.

Each morning, George sets his alarm for 3:30 a.m.—not out of necessity, but out of pride. At that hour, the park is hushed and still. The air carries a gentle breeze, and the stars shimmer above the banyan trees. There’s no movement, no footsteps—just the kind of silence you can almost hear. By 4:15, a couple arrives for their daily walk, always on schedule. George is already seated upright on the bench, his blanket folded and stowed away, appearing more like an early commuter than a man who slept outdoors. They exchange greetings every morning—a quiet acknowledgment of mutual respect. I joked that maybe the couple should move their walk an hour later so George could get some extra sleep. He chuckled and said, “That would be perfect,” a smile on his face. “I’d get another hour each morning.”

It was one morning, just as the alarm sounded at 3:30, that George opened his eyes and saw a shadow moving on the roof of Paki House. From the bench, he had a clear view—something he wouldn’t have had from the terrace. Trusting his instincts, he remained quiet and dialed 911.

Within minutes, five police vehicles converged on the building. They apprehended the suspect—a man they had been looking for. “It was a coincidence,” George said, “but the timing was just right.” His early wake-up habit had unexpectedly turned into a force for good.

A few days later, officers returned with food and sincere thanks. George had helped close a case. The man who sleeps on a bench had become, once again, a quiet guardian of the space around him.

We spoke about morality and principle, and how he chooses solitude not out of fear, but out of clarity. He knows where to draw the line. He doesn’t compromise on his peace or his values. In What If It Is True, he writes:

“It is not the world that defines your character—it is what you do when the world watches and when it doesn’t.”

George spoke passionately about the importance of standing up for what you believe in—even when it isn’t easy. His convictions were shaped early by the example of his parents during World War II. Though they weren’t soldiers and had no weapons, they used their knowledge of Morse code to relay messages to British forces whenever they spotted German submarines departing from the port of Marseilles, likely en route to Gibraltar. “They knew what the Nazis were doing was wrong,” George said. “They couldn’t just watch.” That sense of duty—to oppose wrongdoing and help those who fight it—runs deep in George’s worldview. It’s why he avoids bad company without negotiation. “If bad people approach me, I don’t tell them anything,” he said. “I just walk away.” It’s also why he refuses government housing, knowing it could mean living among troublemakers. “George, we can give you an apartment,” they tell him. “Yeah,” he replies, “but surrounded by whom?” For him, choosing the bench at the bus stop isn’t just about shelter—it’s about choosing solitude over compromise. “I only want good people around me,” he said. “That’s non-negotiable.”

Children brought by their parents sometimes sit with him, listening to stories about right and wrong. George believes teaching others to be good is one of the most meaningful things a person can do. “Kindness matters,” he said. “It matters at any age.”

I shared a little about my own life—my mornings swimming in the ocean, my afternoons writing about meditation and emotional healing, my walks through the park reflecting on the nature of reality. As we spoke, we found ourselves reaching the same conclusion: that in retirement, we’ve both found a calling not of leisure, but of legacy.

“Now is the time to speak,” George said. “Now is the time to show what we’ve learned.”

I couldn’t agree more. Through my website, I aim to guide individuals toward personal growth, fulfillment, and inner peace. Through his books, George shares a message shaped by lived experience and unwavering moral clarity. Different mediums, same mission: to help others become better versions of themselves.

In Stardom To Gloominess, George writes:

“Ms. Life pushes a man to his knees, onto a razor-sharp state of desperation. But at the end, she prizes him with a life worth living.”

As I got up to leave, I stepped from the porch and noticed the patrol car stationed just a few feet away. The officers inside gave me a wide, knowing smile. They understood I’d been talking with George—and they respected him for it.

That smile said everything.

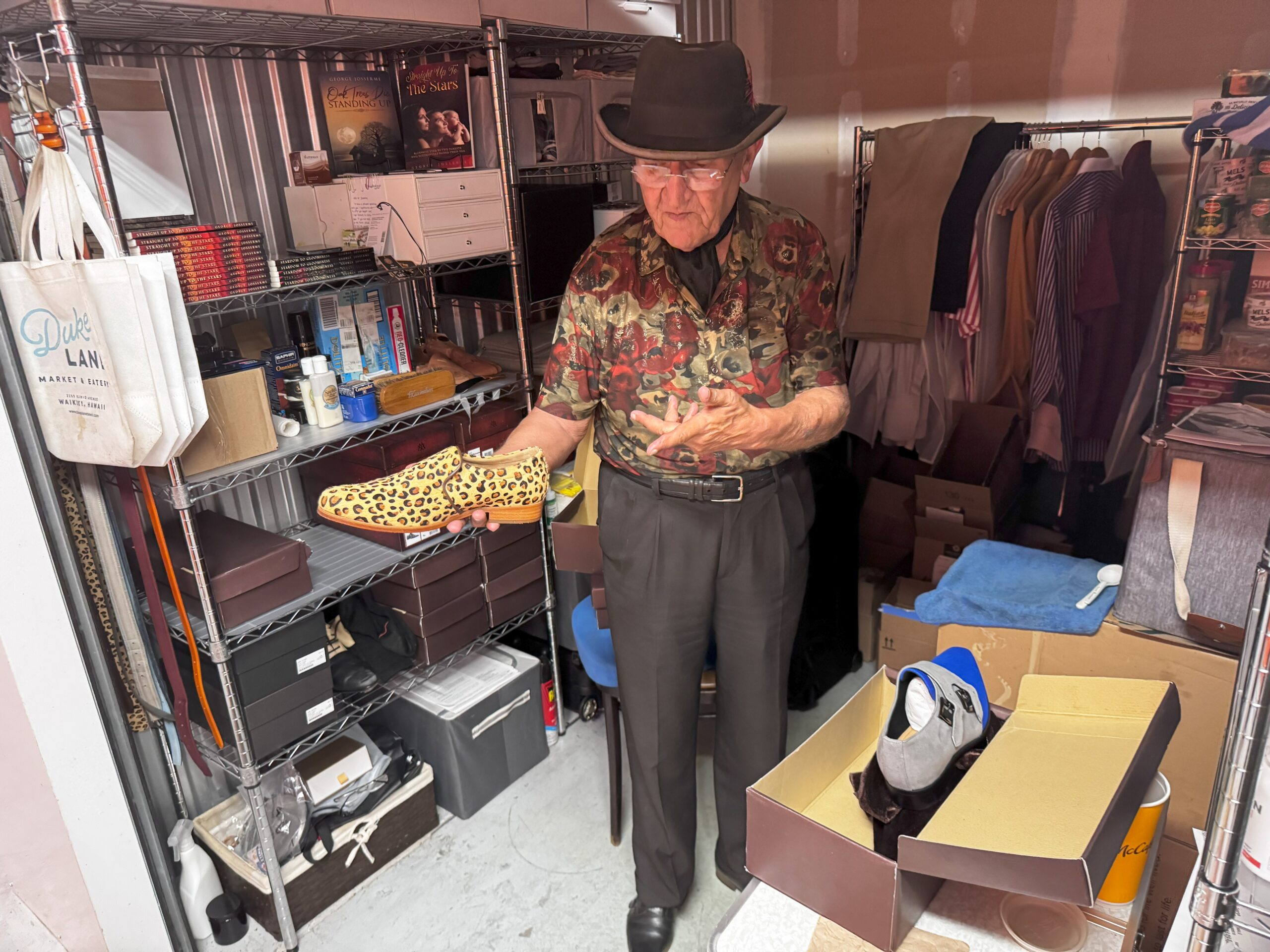

I have not seen George for the past two days. On July 29, Hawaii issued a tsunami warning, prompting me to visit him in person to alert him to the impending danger, as I was unable to reach him via phone—his mobile device had malfunctioned, and a replacement, ordered online, had yet to arrive. Consequently, our communication remains limited to in-person encounters in the park. George adheres to a regimented daily routine; he awakens promptly at 3:30 a.m. each morning and proceeds to a nearby McDonald’s to procure his coffee and breakfast. Recently, he visited a physician; although his health remains sound, the doctor advised him to adopt a more nutritious diet, as fast food from McDonald’s is inherently unhealthy. In response, George ordered a portable cooler online. When he attempted to retrieve it from the UPS Store, he discovered it was too large to transport via bus, as the driver refused to permit its carriage. We mutually agreed that my wife would collect the cooler from UPS and escort George to his storage unit the following day. Accompanying him, we observed the storage, which was meticulously organized—shoes stored in boxes, suits hanging on racks, and an array of books.

When asked about his footwear sources, George recounted an extraordinary story: all his shoes are handcrafted in France by a family-run shoemaking enterprise that has been making shoes for him since he was ten years old. The original proprietors’ descendants now operate the business, continuously producing bespoke footwear that fits him perfectly. His sartorial style is distinctly unique; his hat, scarf, shirt, trousers, and shoes all reflect an individualistic aesthetic. He displayed a tailored suit, inscribed with: “Specially Tailored For George Josserme.”

His distinctive appearance often captivates tourists on Kuhio Avenue, particularly when he sells his books; curiosity about his attire prompts many to purchase out of intrigue. This raises the question: what does this fascinating individual write? We enjoyed a leisurely lunch at Pyramid Bistro on Nimitz, where George regaled us with stories from his past. In his youth, he toured with an orchestra as a conductor, leaving little time for literary pursuits. Now, however, he feels compelled to explore his artistic talents through writing. He reflected on life’s unpredictable nature, recalling an incident years ago that profoundly moved him and ignited his contemplations on conviction and moral resolve.

He recounted an incident in a coffee shop where he observed someone struggling to breathe and touching his chest. George intervened, inquiring whether he should summon an ambulance. When paramedics arrived, their efficient handling of the situation was remarkable. One of them prescribed medication to the patient, which piqued George’s curiosity, as only licensed physicians are authorized to prescribe drugs. During their conversation, he discovered that the paramedic was a physician aspiring to serve as a first responder, driven by a desire to save lives in emergencies. The paramedic shared his story: despite being a doctor earning a substantial salary, he chose to work on an ambulance with two paramedics—whom he affectionately called “these two lions”—dedicating himself to life-saving efforts for a modest income.

George’s admiration for moral conviction and altruism resonated deeply with his own upbringing. His parents, who had endured the hardships of the post-World War II era, were known for their selfless acts of kindness. They owned a large estate and provided free housing to needy families, many of whom still reside there. After their passing, George inherited the property, valued at approximately eight million euros. He faced a moral dilemma: sell the estate and enjoy a carefree lifestyle in Hawaii or elsewhere, or uphold his parents’ legacy of charity. His conscience compelled him to honor their memory; he could not envision evicting the families who had relied on their generosity.

A legal solution was devised: his French lawyer calculated that, considering the combined income of the 16 residents—many of whom are nearing their eighties—the fair market value they could collectively afford was around five million euros. They agreed to purchase the estate collaboratively. An intriguing discovery emerged during renovation work; documents revealed that the estate once belonged to Napoleon. This historical artifact prompted officials to be contacted, with consequences: if George declined to assume ownership, the French government would claim it as a national heritage site.

George is contemplating a trip to France; however, the prospect is daunting. The allure of the Hawaiian lifestyle, combined with the logistical complexities of such a journey, causes him to postpone his plans repeatedly.